Subscribe now and receive weekly newsletters with educational materials, new courses, interesting posts, popular books, and much more!

Articles

Churchill and the Guns of Singapore, 1941-42: Facing the Wrong Way?

- By CHRISTOPHER M. BELL

- | June 25, 2019

- Category: Churchill and the East Explore

A famous photo of the debacle: Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival (right), walks under a flag of truce to surrender Singapore, 15 February 1942. (Wikimedia)

Winston Churchill described the fall of Singapore as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.”1 On 15 February 1942, around 80,000 British, Indian and Australian soldiers surrendered to a Japanese force roughly half their size. Churchill was horrified. His physician, Lord Moran, recorded afterwards that the Prime Minister “felt it was a disgrace. It left a scar on his mind. One evening, months later, when he was sitting in his bathroom enveloped in a towel, he stopped drying himself and gloomily surveyed the floor: ‘I cannot get over Singapore,’ he said sadly.”2

The Guns of Singapore

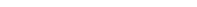

One of the enduring myths of the Second World War is that the massive 15-inch guns defending the island were “pointing the wrong way” when the time came to use them. In this version of events, the Japanese avoided the gun defences simply by attacking from the north, across the narrow Johore Strait, after advancing through Malaya. Singapore’s heavy guns, built to repel a seaborne assault on the island, were sited uselessly on the southern and eastern coasts. The story goes that they could not be turned against an attack from the north.

The reality, however, is that three of these five guns had a full 360-degree traverse. They could and did fire at the Japanese attackers, albeit to little effect. More to the point, the guns served their intended purpose. They did deter the Japanese from attacking from the sea.

Churchill’s Second World War memoirs specifically noted that the island’s guns had been used against the enemy. But indirectly, he contributed to the myth in another way, reinforcing the idea that the northern defences had been shamefully inadequate. He complained in The Hinge of Fate that

“there were no permanent fortifications covering the landward side of the naval base and of the city! Moreover, even more astounding, no measures worth speaking of had been taken by any of the commanders since the war began, and more especially since the Japanese had established themselves in Indo-China, to construct field defences. They had not even mentioned the fact that they did not exist.”3

Who was responsible?

As Japanese forces approached the southern tip of Malaya in early 1942, Churchill was “staggered” to learn the state of the landward defences. “It never occurred to me for a moment,” he wrote to General Ismay, “that the gorge of the fortress of Singapore, with its splendid moat half-a-mile to a mile wide was not entirely fortified against an attack from the northward.”4

Who was to blame for this state of affairs? Churchill acknowledged that as prime minister and minister of defence he must bear a share of the responsibility. “I ought to have known,” he wrote after the war. “My advisers ought to have known and I ought to have been told, and I ought to have asked.” Yet “the possibility of Singapore having no landward defences no more entered into my mind than that of a battleship being launched without a bottom.”5

Churchill’s advisers knew that Singapore had little in the way of local defences. The reasons for this deficiency stretch back to the early 1920s, when the decision was first taken to build a naval base there. At that time, landward defences for the island were considered unnecessary. Military authorities assumed that southern Malaya’s difficult terrain, dense jungles, and poor roads ruled out an attack on Singapore from the north.

Between the wars

Churchill was aware of this. As Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1924 to 1929, he took an active interest in the development of the naval base. Indeed, he was one of the few to express doubts about Singapore’s immunity to a landward assault. In January 1925, he said the Japanese could be expected to “make elaborate plans for a landing on the mainland and an attack on Singapore from that direction. They might possibly be able to construct tanks or other mechanical contrivances which would be capable of drawing guns through the forest.” But the Chief of the Imperial General Staff insisted that a large-scale landward attack “was impossible,” and Churchill did not press the matter.6

Repulsing a seaward attack was itself the subject of lively debate between the wars. The army and the navy both wanted large coastal guns as the backbone of the defences; the Royal Air Force proposed to rely on aircraft. Planes were considerably less expensive than permanent fortifications, and would not even need to be present in peacetime. Churchill, always eager to secure reductions in defence expenditure, was attracted to the idea aircraft as Singapore’s main defence, although this did not prevent the installation of heavy guns during the 1930s.

The expectation of a seaborne assault was finally cast away in 1936-37, when investigations launched by General William Dobbie, the General Officer Commanding, Singapore, revealed that it was possible for the Japanese to land a substantial force in Malaya and then advance south to attack the island fortress. If the enemy succeeded in occupying southern Malaya, the naval base at Singapore would be vulnerable to aircraft and artillery fire, rendering it all but useless.

As war approached

Defence plans had to be completely recast over the next few years, as it now appeared that the naval base and island could only be secured by keeping the attackers far to the north. All Malaya would need to be defended. This meant a substantial increase in troops and aircraft allocated to the theatre. The timing for Britain could not have been worse. Resources for the Far East were already in short supply, and would become even scarcer once the war in Europe began. Italy’s entry into the conflict and the fall of France in 1940 left little choice but to concentrate on the defeat of Germany and Italy.

Churchill had long been skeptical about the likelihood of Japan risking war with Britain and the United States. With British and Commonwealth forces hard-pressed by the Axis in North Africa, he had no intention of diverting badly-needed troops and aircraft to reinforce Malaya and Singapore—a distant theatre where they might never be used. As the danger of a Japanese attack mounted, Churchill continued to resist pressure to augment Singapore’s defences.

The Chiefs of Staff in London were nevertheless committed to the plan to hold all of Malaya. In Singapore, where military commanders were preparing to fight the Japanese far to the north, there was little incentive to allocate resources to local defences. On the contrary, by early 1941 military authorities had shifted their gaze even further northward. The most serious threat increasingly appeared to be a Japanese invasion of neutral Thailand (Siam), which would allow them to establish air and land bases from which to launch an assault on Malaya.

Operation Matador

The British answer was Operation Matador, a pre-emptive occupation of southern Thailand to prevent the Japanese from gaining a foothold in the Kra Isthmus. This required British forces to race across the Thai frontier as soon as a Japanese invasion force was detected crossing the South China Sea.7

The plan approved by the Chiefs of Staff received Churchill’s assent in April 1941. He informed General Ismay that he had “no objection in principle to preparing the necessary plans for holding this forward position in the north, but we must not tie up a lot of troops in these regions.” Operation Matador’s forward defence, he noted, meant that Britain was no longer “attempting to defend Singapore at Singapore, but from nearly 500 miles away.”8

But Operation Matador was never launched. A Japanese convoy was spotted at sea on the morning of 6 December, but the British could not be certain of their destination. The convoy might have another destination, or just a bluff to lure the British into invading a neutral state. The British hesitated, and it was soon too late to beat the Japanese to the Kra Isthmus.

Japan triumphs

The defence of Malaya went badly from the start. The Japanese pressed relentlessly southward and by mid-January 1942 it was clear that British forces would be driven out of Malaya entirely. Churchill exhorted local commanders to defend Singapore to the last. “I want to make it absolutely clear”, he wrote to General Wavell, “that I expect every inch of ground to be defended, every scrap of material or defences to be blown to pieces to prevent capture by the enemy and no question of surrender to be entertained until after protracted fighting among the ruins of Singapore City.”9

Churchill was understandably dismayed when he discovered the true state of Singapore’s defences. He had believed the Japanese army would soon face a new and formidable line of obstacles. Instead, he learned that the campaign was already virtually lost. There would be no heroic last stand.

Postwar reflections

This blow to British prestige remained a sore spot long after the war. In late 1948, General Henry Pownall, part of the research team that helped Churchill compile his memoirs (and Wavell’s chief of staff during the Battle of Singapore), carefully explained the reasons why the island’s defences had been so weak in 1942.10 Churchill was not convinced. “I am aware”, he wrote,

of the various reasons that have been given for this failure: the preoccupation of the troops in training and in building defence works in Northern Malaya; the shortage of civilian labour; pre-war financial limitations and centralized War Office control; the fact that the Army’s role was to protect the naval base, situated on the north shore of the island, and that it was therefore their duty to fight in front of that shore and not along it. I do not consider these reasons valid. Defences should have been built.

In fact, the reasons Pownall offered are compelling. Why would Churchill reject them? He certainly had an incentive after the war to deflect attention from his role in withholding military resources from the Far East. However, the fall of Singapore had been such a profound shock in 1942 that his reaction to Pownall’s explanation may have been more emotional than reasoned.

Endnotes

1 Winston Churchill, The Hinge of Fate (London: Cassell, 1951), 43.

2 Lord Moran, Churchill: The Struggle for Survival 1940–1965 (London: Constable, 1966), 27.

3 Churchill, Hinge of Fate, 43.

4 Churchill to Ismay and Chiefs of Staff, 19 January 1942 in Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, Vol. 17 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2014), 106.

5 Churchill, Hinge of Fate, 43.

6 CID Sub-Committee on Singapore, SP (25), minutes of first meeting, 16 January 1925, CAB 16/63, The National Archives.

7 Cf., Ong Chit Chung, Operation Matador (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1997).

8 Churchill to Ismay, 10 April 1941, The Churchill War Papers, ed. Martin Gilbert (New York: Norton, 2000), pp. 475-6.

9 Churchill to Wavell, 20 January 1942, Churchill Documents, vol. 16 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2011), 112.

10 Cat Wilson, Churchill on the Far East in the Second World War (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 83-85; David Reynolds, In Command of History (London: Allen Lane, 2004), 294-97.

Further Reading

How Churchill Waged War, by Allen Packwood, reviewed herein by Terry Reardon.

The Author

Christopher M. Bell is a Professor of History at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He has published widely on twentieth century naval history. His most recent work is Churchill and the Dardanelles.

No short summary account of why the abject surrender at Singapore of a British Commonwealth Army of 130,00 to a Japanese Army of less than 30,000 came about can be regarded as entirely satisfactory unless it draws a significant distinction between “defences” and “defenders” – the men and their leaders, especially GOC Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival.

Profound shortcomings in these latter respects account for the immediate “profound shock” and its lingering emotional resonance experienced by Churchill following that surrender. Professor Bell’s focus is plainly on “defences” rather than “defenders,” as is that of Lieut.-General Pownall in the paper which is the primary source for Bell’s analysis (Appendix D of “Hinge of Fate”).

Consequently, when he quotes Lord Moran on Churchill’s dejection he leaves out Moran’s perception that the surrender was, for his patient, “something more than a reverse. I think he wondered if it were a portent. It is the will to fight that counts in war. That, in some measures, was missing at Singapore.”

On General Percival’s qualities as a wartime commander, Bell, and the Pownall paper he quotes, have nothing to say. Professor Reynolds, another of Bell’s principal sources, confines himself to the graphic, if single-word description: “hapless.” To any readers not familiar with his work, I commend the distinguished military historian Keith Simpson, and his study of Percival in “Churchill’s Generals” (ed. John Keegan, pub. London: Abacus, 1999). There is space, I think, to quote two items from Simpson’s closing paragraphs.

First, an opinion of his own: “Percival cannot be held responsible for the strategic, political and military decisions taken with regard to the defence of Malaya and Singapore, but he can be criticized for his failings as a military commander…. For the Japanese the campaign until the very final moment … was a close-run thing, and it is possible that a military commander of Mongomery’s or Slim’s calibre might have prolonged the defence of Malaya permitting the necessary build-up of reinforcements in Singapore for a decisive counterstroke.”

Second, an opinion quoted by Simpson from the diaries of none other than General Pownall: “We were frankly out-generalled, outwitted, and out-fought.”

In my opinion, which challenges that expressed by Professor Bell in his closing paragraph, there were very good reasons for Churchill’s emotion in respect of the Singapore capitulation.

I commissioned this piece specifically to address the belief that Singapore’s guns were pointed the wrong way, not as a capsule history of the debacle. If you are suggesting that Churchill’s shock and dismay over the fall of Singapore was mostly about the shortcomings of troops and commanders, not the state of the local defenses, that is a valid point. There were a lot of British defeats early in the war that shook Churchill’s faith in the fighting qualities of the British. But it misses the point. Professor Bell had 2000 words specifically to address the “guns pointing the wrong way” myth, and that’s all he attempted to do. A full account of Churchill’s reaction to the fall of Singapore would have to take much wider view, and would include the sorts of issues you seem to think we overlooked.

I concur with Mr. Attenborough’s deductions in their entirety. What lacked most of all was the will to win, or more simply, the fighting spirit. Quality of command was a far greater issue than the guns and the direction they pointed in. I don’t hold the troops accountable at all, their commanders were ultimately responsible. I wonder how many of those brave men would have preferred to fight and die rather than surrender?

I have faced that question a few times in my own military career, and I decided “death was not the worst of evils.” Oddly, when the fear of death weighed less than the fear of failure, neither death nor failure occurred…I wish with all my heart Percival would have come to a similar conclusion rather than his own to surrender.

Mr. Churchill’s disappointments plague me and I feel sorry for him that he wasn’t surrounded by more of his own kind…brave men, courageous and too proud to give up.

Hmm i believe I read that the guns could be turned around BUT would do no good anyway as the shells against moving enemies would be near useless. Read it in a great book called “the Decline and Fall of the British Empire” by Piers Brendon.

It is true that 3 of the 5 15inch guns in the south and east of Singapore island had a 360 degree traverse but they were completely ineffective for two reasons: they only had armour-piercing shells in the expectation of being used against enemy warships and they were firing blind because the gun crews had no fire directors. One of the Japanese accounts records one of the shells falling in the north of the island as they advanced which made a very large hole in the soft ground but did not cause any casualties.

Noel Baptiste is quite correct. Over the years I had many coversations with men from the 155th [Lanarkshire Yeomanry]Field Regt RA who, with bravery and distinction, had fought and resisted the Japanese advance down through Malaya and onto Singapore. The fact that General Percival had located them in the North East of the Island—the point he [mistakenly] expected the Japanese attack is a case in point. What infuriated the Gunners was that they were forever to be known as “cowards.” This they most certainly were not. There were indeed deficiencies in the leadership, both before the Japanese attack in December 1941 and after it. But the rank and file did nothing to deserve this slur. And neither Churchill nor any other leading politician did anything to correct this. It is fair to say that Churchill was not popular among the tens of thousands of brave men who were to later suffer the horror of Japanese hell camps.

Percival to Wavell, 15 February 1944 (reprinted by Churchill in his war memoir The Hinge of Fate): “All ranks have done their best and are grateful for your help.” The bravery not only of British but of Australian, Indian and other defenders of Singapore was demonstrable. Churchill couldn’t commend every unit in the army, and he never called gunners “cowards.” Nevertheless there was in fact quite a good deal of cowardice and very bad behavior amongst certain troops in that campaign. Churchill’s Singapore Chapter 6 in The Hinge of Fate is a fair representation of events as he observed them. It begins:

Many of the 130,000 “British’ soldiers were colonial troops, and several Indian regiments fought with profound distinction in Malaya. The British had essentially no armor, not like the Japanese, who had several panzer divisions, and each time they came to a geographic line of defense, their modest armor contingent invariably proved decisive. Perhaps it’s not so much that Percival was bad but that he was stunned, as was most of the world, by Japanese seriousness and professionalism.